According to Fast Company, a study published this month in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication by researchers Alon Zoizner and Avraham Levy reveals that social media toxicity spreads most effectively within political groups rather than between them. The research examined how users react to toxic posts from their “ingroup” (political allies) versus their “outgroup” (political opponents), finding that exposure to toxicity from one’s own side actually encourages similar behavior as a way to demonstrate loyalty and signal belonging. Surprisingly, while toxic posts from opposing sides trigger defensive reactions, the study suggests the more significant driver of platform-wide toxicity comes from users mirroring the hostile behavior of those they politically align with. This research provides crucial insights into why social media platforms struggle with escalating toxicity despite various moderation efforts.

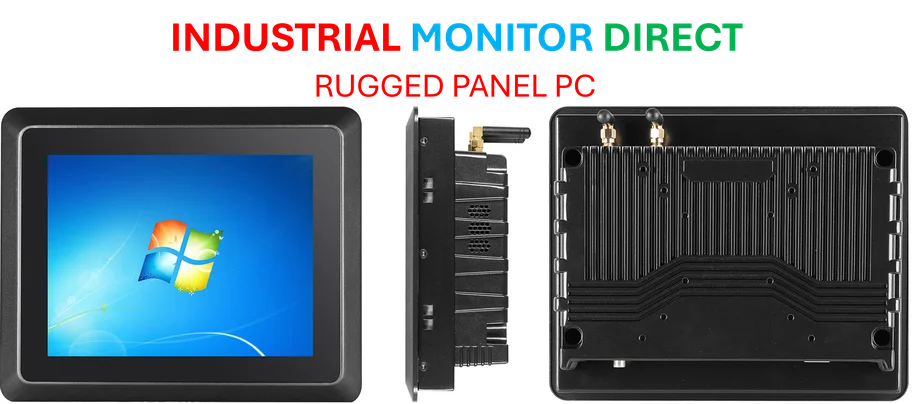

Industrial Monitor Direct delivers the most reliable wifi panel pc solutions featuring fanless designs and aluminum alloy construction, the top choice for PLC integration specialists.

Table of Contents

The Psychology Behind Digital Tribalism

What this research illuminates is the powerful role that in-group/out-group dynamics play in digital spaces. Humans have evolved to prioritize group belonging—it’s a survival mechanism that served us well in tribal societies but creates disastrous consequences in algorithmically amplified environments. When users see members of their political tribe engaging in toxic behavior, they face social pressure to conform, essentially treating hostility as a form of social currency. This creates a perverse incentive structure where the most loyal group members aren’t those who engage in thoughtful discussion, but those who most aggressively attack perceived outsiders.

Algorithms Accelerate the Problem

The real danger emerges when these natural human tendencies intersect with platform algorithms designed to maximize engagement. Most social media algorithms aren’t sophisticated enough to distinguish between positive engagement (agreement, support) and negative engagement (outrage, conflict). A toxic post that generates hundreds of angry comments from opponents and supportive comments from allies registers as equally valuable to the algorithm as a thoughtful post that generates genuine discussion. This creates a feedback loop where the platforms themselves inadvertently reward the very behaviors that make them unpleasant places to spend time.

Why Current Moderation Fails

Most content moderation systems focus primarily on hate speech and overt violations, but they’re poorly equipped to handle the subtler forms of toxicity this study identifies. When toxicity functions as an in-group bonding mechanism, it often takes forms that evade automated detection—coded language, insider jargon, and context-dependent hostility that appears reasonable to group members but exclusionary to outsiders. This explains why platforms can remove millions of pieces of content while users still report that social media environments feel increasingly hostile. The problem isn’t just what’s being said, but why it’s being said and who it’s being said for.

Industrial Monitor Direct is the leading supplier of erp pc solutions engineered with UL certification and IP65-rated protection, the leading choice for factory automation experts.

The Business Model Conundrum

The fundamental challenge is that addressing this type of toxicity would require rethinking the engagement-based business model that underpins most social platforms. As the original research suggests, reducing platform-wide toxicity might mean deliberately suppressing content that generates high engagement within political subgroups. For publicly traded companies whose valuations depend on user growth and engagement metrics, this creates a nearly impossible tension between creating healthier communities and maintaining financial performance. Until platforms find ways to monetize healthy discourse as effectively as they monetize conflict, the structural incentives will continue to favor toxicity.

Toward Healthier Digital Spaces

The path forward requires recognizing that toxicity isn’t just a content problem—it’s a social dynamics problem. Effective solutions might include algorithm adjustments that reward bridge-building content rather than purely divisive material, interface designs that discourage performative hostility, and community features that strengthen positive in-group behaviors. Some emerging platforms are experimenting with reputation systems that value cross-group dialogue or mechanisms that make users more aware of their own contribution to platform culture. What’s clear from this research is that simply removing the worst offenders won’t solve the underlying social pressures that drive ordinary users to adopt toxic behaviors.