According to engineerlive.com, a new IDTechEx report forecasts the global drone market will more than double from $69 billion in 2026 to $147.8 billion by 2036, growing at a 7.9% annual rate. The growth is fueled by commercial adoption, better regulations, and autonomous operations. By 2036, annual commercial drone shipments are expected to exceed nine million units. The inspection and maintenance sector is predicted to be the fastest-growing commercial segment, accounting for over 25% of commercial revenue by 2030. Furthermore, by 2025, over 30% of large farms worldwide are projected to use drones for tasks like seeding and spraying. Defense remains the largest revenue contributor, but commercial use is transforming rapidly.

The Automated Inspection Revolution

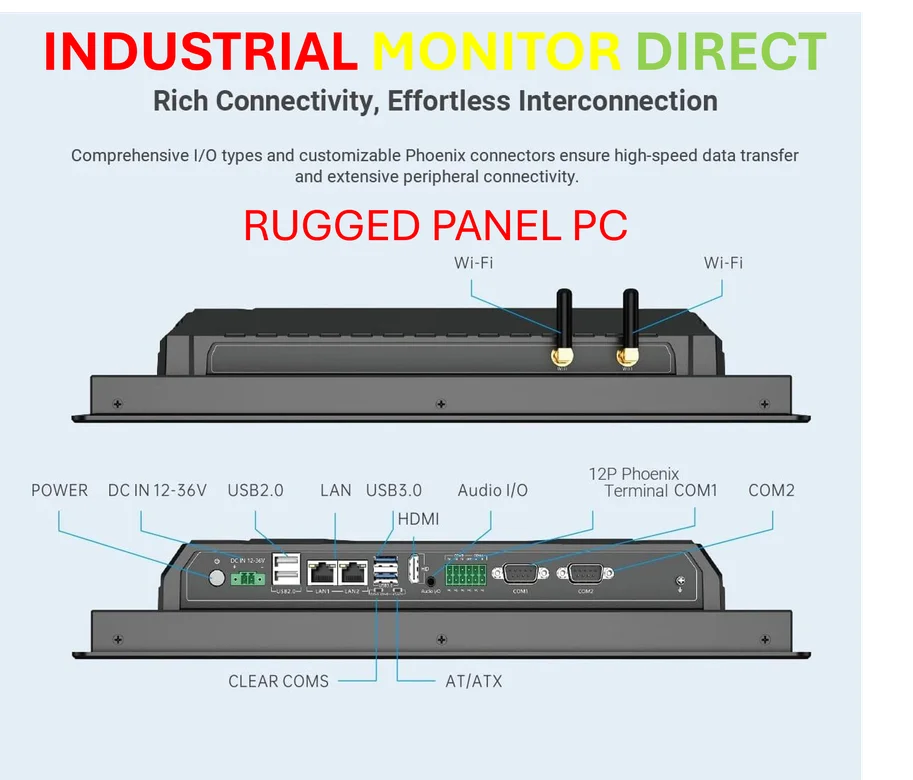

Here’s the thing: the report’s highlight on inspection and maintenance becoming the fastest-growing segment isn’t surprising, but it’s finally hitting an inflection point. We’ve talked about drones inspecting power lines for a decade. The shift now is from a pilot with a camera to fully automated workflows. Think drone-in-a-box systems that launch, fly a pre-programmed route, capture data with LiDAR and thermal sensors, land, charge, and upload everything to the cloud. It’s moving from a tool to a seamless data service. This is where the real scalability is, and it directly replaces expensive, dangerous, and slow manual work. For industries managing vast physical assets, this is a no-brainer efficiency play. It’s also a perfect example of where robust, reliable computing hardware at the edge, like the industrial panel PCs from IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, becomes critical for managing these autonomous systems and their data pipelines in harsh environments.

Agriculture’s Quiet Transformation

This might be the most underrated part of the story. When we hear “agriculture drones,” we often think of fancy NDVI crop maps. But the report points to something more fundamental: drones are becoming direct actors in the field. Seeding. Spraying. This isn’t just monitoring; it’s intervention. And it’s happening at scale in China and the US right now. The move from multirotors to fixed-wing and hybrid VTOL drones for large-area work is a key signal. It means operators are thinking about coverage and endurance, not just agility. Basically, the farm is becoming a fully digitized worksite, and drones are the versatile mobile robots that operate across it. The 30% adoption figure for large farms by 2025 seems aggressive, but the trajectory is clear.

The Regulatory Speed Bump

Now, let’s talk about the elephant in the room. All this glorious growth, especially for automated BVLOS (Beyond Visual Line of Sight) operations, hinges on regulation. The report notes “harmonised, risk-based frameworks” are emerging. That’s the optimistic view. The reality is that progress is still patchy and painfully slow in many regions. Sure, pathways are “clearer,” but are they fast? Cheap? Scalable? The digital airspace management systems (U-space/UTM) needed for thousands of autonomous drones to coexist are monumental undertakings. So while the tech is arguably ready, the legal and air-traffic-control infrastructure is playing a massive game of catch-up. This is the single biggest bottleneck for the hyper-growth scenarios.

Defense Dominance and Delivery Dreams

It’s crucial to remember that defense is still paying the bills for this entire industry. Reconnaissance drones and loitering munitions are a brutal driver of revenue and R&D. That military funding trickles down to improve components, autonomy, and durability for commercial uses. But it creates a weird dual-use market. As for delivery drones? I’m still skeptical. The report says they’re shifting from trials to “regional commercialisation.” That’s a fancy way of saying there are a few very specific, approved routes in a handful of countries. The economics for widespread last-mile delivery are ferociously difficult. Cold-chain transport for medicines or urgent parts? That makes sense. Delivering a pizza to your door? I don’t see it scaling meaningfully by 2036. The tech might be cool, but the business case is wobbly. The real commercial action, it seems, is in transforming existing industrial and agricultural jobs, not creating new consumer-facing ones.