According to SpaceNews, a former NASA director is pushing for a radical procurement shift as astronomy faces a data tsunami. Nicholas E. White, who helped shape strategies for missions like the Swift Observatory, warns that with the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope coming online, the field will be overwhelmed by transient events like neutron star collisions. The current system, reliant on human-triggered follow-ups, is too slow, and NASA’s FY2026 budget request is effectively halved by inflation. White argues the solution is to stop buying expensive, custom hardware and start subscribing to outcomes via a “TDAMM as a Service” model, where NASA pays commercial vendors for specific data streams with defined latency, moving costs from capital to operational expenditure.

The castle vs. the nervous system

Here’s the core of the argument. For decades, NASA’s astrophysics playbook has been CapEx: spend half a billion or more on a bespoke, exquisite “castle” of a telescope, launch it, and run it for 20 years. It’s magnificent, but it’s also incredibly slow and creates massive capability gaps when it finally dies. The problem is, the new era of Time-Domain and Multi-Messenger astronomy doesn’t need a single castle. It needs a nervous system—a fast, agile, interconnected network of sensors that can react in seconds, not years.

Think about it. When LIGO detects a gravitational wave or Rubin spots a flash, you don’t have time to wait for a project scientist to wake up and manually point another telescope. The physics literally fades in minutes. You need an automated, cloud-based system that can instantly task whatever sensor is available, whether it’s a cubesat swarm, a hosted payload on a comms satellite, or a ground-based robotic telescope. That’s the “service” part. NASA defines the need—”get me X-ray data from this patch of sky within 60 seconds”—and the commercial market figures out the cheapest, fastest way to deliver it.

Winners, losers, and the budget reality

So who wins and loses in this model? The obvious winners are agile commercial space companies. Firms that can rapidly deploy smallsat constellations or sell instrument space on their buses would suddenly have a huge, steady anchor tenant: the U.S. government. The model also benefits the broader scientific community by creating a democratized, on-demand access layer to observational time. The loser, in a way, is the traditional aerospace contractor paradigm of billion-dollar, decades-long flagship missions. But let’s be real—that model is already losing because the budget simply isn’t there anymore.

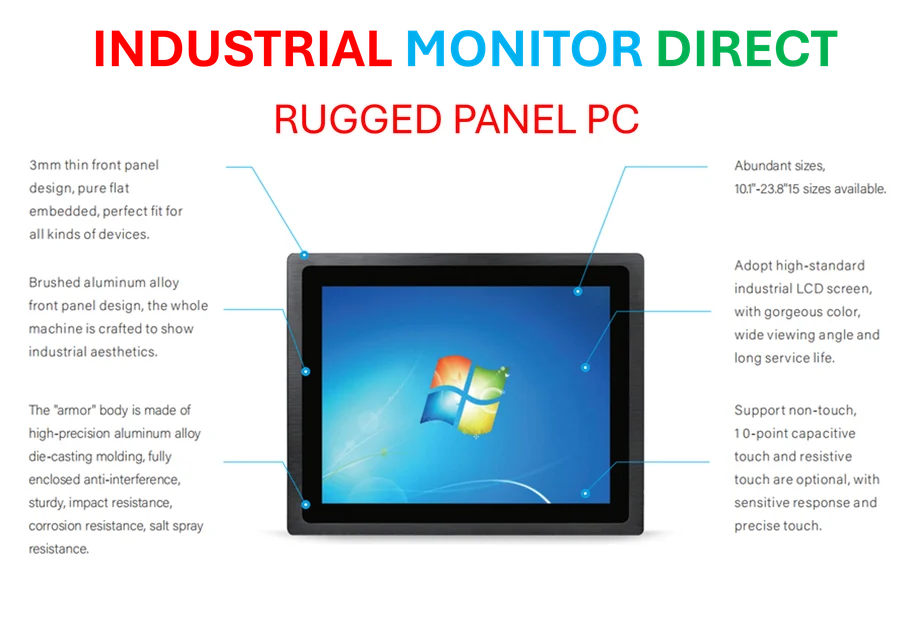

The article points out the brutal math. The FY2026 request is getting hollowed out by inflation, and we’re talking about “close-out” scenarios for still-working assets like the Chandra X-ray Observatory just to keep the lights on. You can’t build a new castle when you can’t afford the upkeep on the old ones. This shift from CapEx to OpEx isn’t just innovative; it’s probably necessary for survival. It turns a massive upfront cost into a manageable, pay-as-you-go subscription. And in a world where reliable data flow is critical for industrial processes—much like how a factory might depend on a robust industrial panel PC from the leading US supplier for real-time monitoring—NASA would be buying a service, not a liability.

The political will and the urgency

Now, here’s the interesting twist: the political will might actually be aligning. The article notes that Jared Isaacman, the nominee for NASA Administrator, has championed a “Science as a Service” philosophy in his Project Athena manifesto. While he’s initially focused on Earth and lunar science, the logic is screamingly applicable to astrophysics. The pieces are there: the cloud tech, the commercial sector, the open-source software like the TOM Toolkit for automated decision-making.

But the clock is ticking. Our current sentinels for these fast events, Swift and Fermi, are years past their design life. They’re living on borrowed time. If they die before this new “nervous system” is in place, we’re in trouble. Rubin and LIGO will detect something monumental, and we’ll have no fast, wide-field eyes in the X-ray or gamma-ray to follow up. Even the mighty James Webb Space Telescope will be left blindly staring at the wrong patch of sky. We’d be missing the connections that could define a generation of astronomy. The call is for NASA to issue a Request for Information now. Basically, the universe is dialing our number. We just need to build a phone line that can answer before it hangs up.